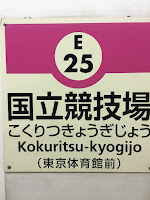

Right next to Meiji Jingu Gaien (明治神宮外苑), where crowds are currently flocking to check out the beautiful yellowing ginkgo trees, is the National Stadium - or part of it at least. The National Stadium (Kokuritsu Kyōgijō=国立競技場) was originally built in 1958 for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics but, following the announcement that Tokyo had won the 2020 Olympics, plans were made to build a new, bigger stadium to be the main venue for the games. Demolition of the old stadium was completed in May 2015 but the original plans were scrapped only two months late amid a public outcry over skyrocketing costs. New, cheaper bids were invited and construction belatedly began in December 2016. As the picture below shows, work is well under way and the new stadium is scheduled to be ready by November 2019 - unfortunately too late for the Rugby World Cup by a couple of months.

Right next to Meiji Jingu Gaien (明治神宮外苑), where crowds are currently flocking to check out the beautiful yellowing ginkgo trees, is the National Stadium - or part of it at least. The National Stadium (Kokuritsu Kyōgijō=国立競技場) was originally built in 1958 for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics but, following the announcement that Tokyo had won the 2020 Olympics, plans were made to build a new, bigger stadium to be the main venue for the games. Demolition of the old stadium was completed in May 2015 but the original plans were scrapped only two months late amid a public outcry over skyrocketing costs. New, cheaper bids were invited and construction belatedly began in December 2016. As the picture below shows, work is well under way and the new stadium is scheduled to be ready by November 2019 - unfortunately too late for the Rugby World Cup by a couple of months.The controversy over costs - the original stadium, even after refinements, was going to cost some 300 billion million yen (three times the cost of the Olympic Stadium in London) - highlights the public's unease over wasteful public spending. On the other hand, there seems to be little popular concern over Japan's spiralling national debt. The figures are staggering: Japan has the highest ratio of debt to GDP by far at 234.7% (way above Greece in 2nd place). The result is that Japan uses an unbelievable half of all tax revenues to service its debt. This may seem odd given Japan's reputation as a "nation of savers" but it is actually Japan's savers - the people buying government bonds - who have basically funded the nation's huge debt. The worry is that with Japan's household savings rate dropping into negative territory in 2014 for the first time since 1955, coupled with a plummeting population and lack of a migration policy, Japan's national debt is unsustainable. The Olympics is only likely to exacerbate the problem.